The bike lane conundrum

Why it's so hard for cities to become cycling cities

An unfortunate pattern is playing out in many cities in North America:

Cities start building bike lanes.

Drivers complain that the bike lanes are taking away driving lanes and increasing congestion.

Politicians listen to these complaints and stop building new bike lanes, and sometimes remove bike lanes that have already been built.

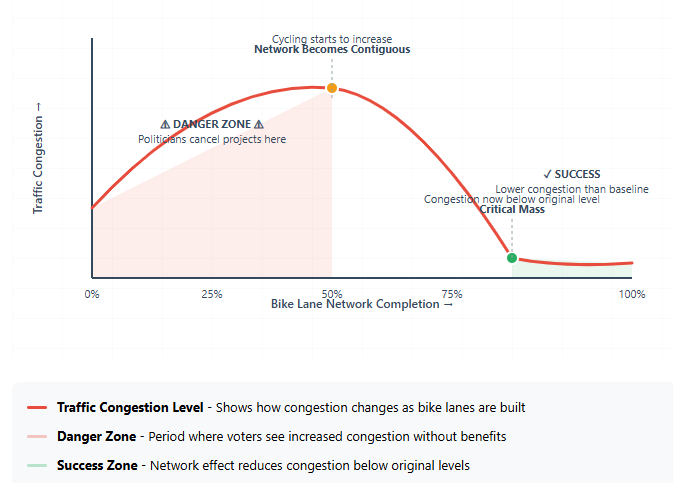

The reason this is unfortunate is that bike lanes do reduce traffic congestion, but not right away. It takes time. Why?

In order to convince enough people to cycle instead of drive, there must be a contiguous bike lane network. Put more simply, you must be able to get from origin to destination without any gaps in the bike lane network that would require you to ride without one. As soon as you are forced to ride in mixed traffic, especially on a busy road, you are much less likely to choose to cycle in the first place.

Building a contiguous bike lane network cannot happen overnight. Cities must budget for bike lanes over many years, and there can only be so much contruction at any given time. This creates a situation where bike lanes may increase traffic congestion for an interim period, where some are installed but not yet a full network that will entice more cycling. And that’s the danger zone—where politicians may bow to the outcry from drivers and stop the bike lane network from ever becoming contiguous.

Here’s a graph that shows what this might look like. This isn’t based on data, it’s just meant to give you a visual of the overall situation.

Overcoming this conundrum is difficult because of misaligned incentives. Politicians want to get re-elected, and listening to their voters is a pretty obvious way to increase the likelihood of that happening. And the particular voters who want to keep driving their cars and are frustrated by less lanes are not necessary wrong in the moment. They just don’t have enough information to know that if they were to tollerate the situation for 3-5 years, long enough for a contiguous bike lane network to be completed, things would improve. In fact, there would be even less congestion and more open roads for them to drive on, because enough other drivers would have decided to start cycling instead.

I wish I had a good solution to this conundrum. Education and advocacy make sense, but it’s difficult to convey nuance or complexity when the two sides (drivers vs. cyclists) are already so charged up. Some cities, like Montreal, have overcome the danger zone and seen the positive impact of a more complete bike lane network. Stronger-willed politicians who ignore the complaints of drivers made the difference, knowing that those drivers would eventually get what they wanted anyways.